Why Are We Falling Apart?

The Grand Canyon came to mind when I read a heartbreaking editorial by my favorite columnist, David Brooks. Writing in The New York Times, Mr. Brooks spoke of an America falling apart at the seams. Bad things are on the rise: reckless driving and traffic fatalities, bad behavior in schools, fights on airliners, hate crimes and murders. Charitable giving and attendance at worship services are in decline. And don’t even get started me on American politics. In response to this cascade of woe, Mr. Brooks writes: “What the hell is going on?” The short answer: “I don’t know.” Blog Posted by Robert Bell on March 23rd, 2022

When I first saw the Grand Canyon many years ago, I asked myself the question that every visitor asks. How did this great big, amazingly beautiful hole in the ground get here?

The answer is a story that defies intuition. The Colorado River snakes through the region and lies now at the bottom of the immense canyon. Like all rivers, it carries small bits of stone that chip away at the riversides and river bottom, one tiny spec at a time. Keep that up for a few centuries, and the river slowly deepens its channel.

What makes the Grand Canyon different from the green Hudson River valley is the climate of Arizona. It’s a desert, where only 9 inches (23 cm) of rain fall in an average year, compared with 47 inches (119 cm) on the Hudson. So, the banks of the Colorado River stand in the arid wind, which carries its own load of dust and rock flakes. Over millions of years, these tiny flakes of rock have chipped away at the riverbanks, pushing them outward, turning them into canyon walls as the river dug ever deeper into the ground. And that’s all it took. Water, wind, dust plus millions of years and, hey presto, you get this heart-stopping natural wonder.

The Grand Canyon came to mind when I read a heartbreaking editorial by my favorite columnist, David Brooks. Writing in The New York Times, Mr. Brooks spoke of an America falling apart at the seams. Bad things are on the rise: reckless driving and traffic fatalities, bad behavior in schools, fights on airliners, hate crimes and murders. Charitable giving and attendance at worship services are in decline. And don’t even get started me on American politics. In response to this cascade of woe, Mr. Brooks writes: “What the hell is going on?” The short answer: “I don’t know.”

Mr. Brooks uniquely combines a sharp political mind with deep insight into the human spirit. With the greatest respect for him, I think I do know what is going on. It is what put me in mind of those bits of windblown dust carving a canyon that is 18 miles (29 km) across at its widest point and running for nearly 300 miles (483 km) through Arizona desert.

It is a story of three major disruptions in life over the past 40 years, so big that it is like standing at the foot of a huge mountain and being unable to really see or comprehend its size.

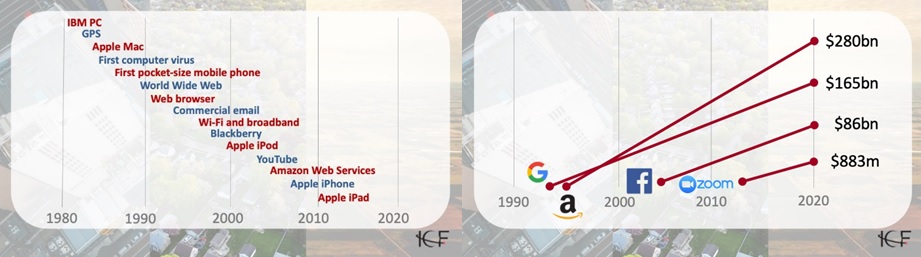

The first wave started, innocently enough, in 1981, when IBM introduced the first computer that could fit on a desk instead of a glass-walled data center. Demand for the IBM PC soon exceeded IBM’s manufacturing capacity, so other companies leaped into the gap. All these PCs came with software called the Disk Operating System or DOS, written by an unknown company called Microsoft. Then, in 1984, another company called Motorola introduced the first consumer-grade mobile phone and Apple, founded in 1976, unveiled its first breakthrough product, the Macintosh computer. Forty years is an extraordinarily short time in which to pack all this technology change. It’s especially short when most of these gadgets and services are what are called “foundational.” That means they didn’t do just one thing – they allowed us to do an enormous range of things in new ways. Typewriters became word processing software. Letters became emails. Library research became a web search. Conversations became social media posts. Videos moved from your TV to the pocket supercomputer that we laughingly still call a phone.

Each advance let us do things faster, better and cheaper, and so each advance became unbelievably popular. From the web browser to email, the Blackberry to the iPhone and iPad, the products created new categories and achieved widespread adoption faster than anything before. The companies that produced them grew their sales faster and bigger than any company in history.

We loved our new tools and toys. But we also were disturbed. People don’t do well when too much changes too fast. Old habits have to be abandoned and new ones created. New evils are created, from cybercrime to revenge porn, and things we trust in become uncertain. People with a grudge gain a megaphone to air their anger. But making it all worse was a second wave of disruption that gave us much more to be angry about.

What is so angry-making? It was an unintended consequence of all that spectacular innovation: people began living in an economy and society shaped by digital technology. But only those could afford to buy it and who had the knowledge to understand it and the skills to use it saw the benefits. That was to have huge impacts.

In 1970, according to research by David Autor, middle-skilled, middle-wage occupations – such as admin support, transportation, retail sales, machine operators, installation and repair – made up 38 percent of all US jobs. Low-skilled, low-wage job (31 percent) and high-skilled, high-wage jobs (30) made up the rest. By 2019, that middle category had dropped 15 points to 23 percent of total employment. Meanwhile, employment in high-skilled occupations grew to 46 percent of the total and low-skilled employment remained unchanged as a percentage of the whole.

To make things worse, average wages for those remaining middle-skilled workers went down compared to the other categories. By 2019, according to Brookings, a shameful 44 percent of Americans worked in low-wage jobs paying a median annual wage of $18,000. What caused it? Sharp growth in automation and the offshoring of manufacturing, which both aimed to reduce what employers paid for low-skilled work and were enabled by the digital revolution.

So, what story do those numbers tell? A large percentage of the working population faced a shrinking market for their skills and slid gradually down the wage ladder. And it is a multi-generation tragedy. Parents’ social and economic status is a good predictor of that of their kids. Parents on the downslope discovered that a key part of the American Dream had been snatched away: their children would not be better off than they were.

So far, this is an American story, since that is what Mr. Brooks wrote about. But these trends are widespread across industrial economies. The middle-skilled, middle-wage workforce is larger in the European Union than in the US, but it has been in steady decline for decades and received a strong downward push in the Great Recession.

So, a large slice of populations in wealthy nations sees themselves on an uninterrupted downward spiral, growing slowly poorer while seeing others grow richer – fabulously so in headlines about tech moguls. Bad enough. But then there came a third wave of disruption called COVID. The global pandemic threw millions out of work, temporarily or permanently. Those who have fared best have been– you guessed it – those who have the knowledge and skills to do work they can do online from home. And as for the rest – best of luck.

My respectful question for Mr. Brooks is: why wouldn’t America be falling apart at the seams. Three great waves of disruption are more than enough. Not every person of modest means is angry and not every angry person is strapped for cash. But the fact is that we have been systematically downsizing opportunity for hundreds of millions of citizens for more than forty years. They are angry about it. They have stopped believing what people in authority tell them. They want change, and they will give their support to anyone who promises it, no matter how empty those promises turn out to be.

There is no mystery to the times we live in. Collectively, blindly, we have created them. All it took was an explosion of innovation, an appalling unwillingness to deal with its darker impacts, and time: the 15,000 days from 1980 until today. Each year, the river carved deeper and the canyon walls moved farther outward. It is not too late to do something about it. We can change the future through our choices. In fact, it is the only thing that can stop it.

How we do it, one community at a time, is a story for my next post.

![]()

![]()

Want to have a voice in iCommunity.ca, the official newsletter of ICF Canada? Please send your blogs, announcements and other interesting content to John G. Jung at jjung@icf-canada.com

ICF Canada 1310-20 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario M5J 2N8 www.icf-canada.com

Contact: John G. Jung at jjung@icf-canada.com 1-647-801-4238 cell

Want to change how you receive these emails?

You can update your preferences or unsubscribe from this list